If All Registered Voters Voted Along Party Lines, Who Would Win -- Democrats Or Republicans?

In every campaign bike, pollwatchers pay close attention to the details of every election survey. And well they should. Merely focusing on the partisan residuum of surveys is, in almost every circumstance, the wrong place to look.

The latest Pew Research Middle survey conducted July 16-26 among 1,956 registered voters nationwide plant 51% supporting Barack Obama and 41% Mitt Romney. This is unquestionably a good poll for Obama – one of his widest leads of the year co-ordinate to our surveys, though largely unchanged from earlier in July and consistent with polling over the grade of this year.

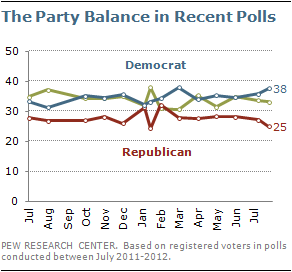

And the survey did interview more Democrats than Republicans; 38% of registered voters said they recall of themselves equally Democrats, 25% every bit Republicans, and 33% as independents (to clarify, some reporters and bloggers incorrectly posted their own calculations of political party identification based on unweighted figures). That'due south slightly more Democrats than average over the past year, and slightly fewer Republicans. Recent Pew Inquiry Middle surveys accept found anywhere from a one-point to a ten-point Democratic identification advantage, with an average of about seven points.

And the survey did interview more Democrats than Republicans; 38% of registered voters said they recall of themselves equally Democrats, 25% every bit Republicans, and 33% as independents (to clarify, some reporters and bloggers incorrectly posted their own calculations of political party identification based on unweighted figures). That'due south slightly more Democrats than average over the past year, and slightly fewer Republicans. Recent Pew Inquiry Middle surveys accept found anywhere from a one-point to a ten-point Democratic identification advantage, with an average of about seven points.

While it would be easy to standardize the distribution of Democrats, Republicans and independents across all of these surveys, this would unquestionably exist the wrong affair to exercise. While all of our surveys are statistically adjusted to correspond the proper proportion of Americans in unlike regions of the country; younger and older Americans; whites, African Americans and Hispanics; and even the right share of adults who rely on cell phones as opposed to landline phones, these are all known, and relatively stable, characteristics of the population that can exist verified off of U.S. Census Agency data or other high quality regime data sources.

Political party identification is another thing entirely. Most fundamentally, it is an attitude, not a demographic. To put information technology simply, political party identification is one of the aspects of public opinion that our surveys are trying to measure, non something that we know ahead of fourth dimension like the share of adults who are African American, female, or who live in the South. Particularly in an election cycle, the residue of party identification in surveys volition ebb and flow with candidate fortunes, as it should, since the candidates themselves are the defining figureheads of those partisan labels. Thus in that location is no timely, contained mensurate of the partisan balance that polls could utilise for a baseline adjustment.

These shifts in party identification are essential to understanding the dynamics of American politics. In the months later on the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, polls registered a substantial increase in the share of Americans calling themselves Republican. Nosotros saw like shifts in the residue of political party identification as the War in Republic of iraq went on, and in the build-up to the Republicans' 2010 midterm election victory. In all of those instances, had we tried to standardize the remainder of party identification in our surveys to some prior levels, our surveys would accept fundamentally missed what were pregnant changes in public stance.

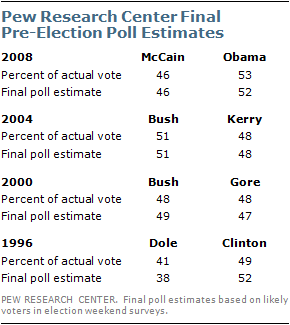

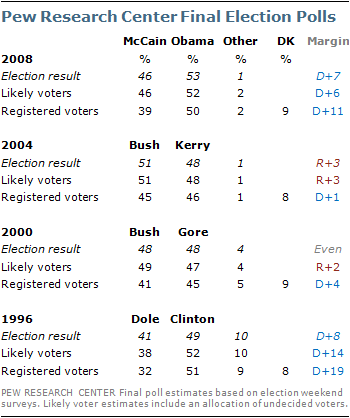

The clearest evidence of this is the accuracy of the Pew Research Center'south final election estimates. In every presidential election since 1996, our final pre-ballot surveys accept aligned with the actual vote consequence, considering we measured ascension Democratic or Republican fortunes in each year.

The clearest evidence of this is the accuracy of the Pew Research Center'south final election estimates. In every presidential election since 1996, our final pre-ballot surveys accept aligned with the actual vote consequence, considering we measured ascension Democratic or Republican fortunes in each year.

In brusk, considering party identification is so tightly intertwined with candidate preferences, any effort to constrain or braze the partisan residual of a survey would certainly shine out whatsoever peaks and valleys in our survey trends, merely would too lead u.s. to miss more fundamental changes in the electorate that may be occurring. In event, standardizing, smoothing, or otherwise tinkering with the rest of party identification in a survey is tantamount to maxim we know how well each candidate is doing before the survey is conducted.

What follows is a more detailed overview of the properties of party identification – how it changes over the brusk- and long-term, and at both the aggregate and individual level. It besides includes a detailed discussion of the distinction between registered voters and likely voters, and why trying to approximate likely voters at this point in the election cycle is problematic.

What is Party Affiliation?

Public opinion researchers generally consider political party affiliation to exist a psychological identification with one of the two major political parties. Information technology is non the same thing as political party registration. Not all states let voters to annals by political party, and fifty-fifty in states that practice, some people may be reluctant to publicly place their politics by registering with a political party, while others may experience they have to register with a party to participate in primaries that exclude unaffiliated voters. Thus, while party affiliation and political party registration is likely to be the same for many people, it will not be the same for anybody.

Party affiliation is derived from a question, typically institute at the end of a survey questionnaire, in which respondents are asked how they regard themselves in politics at the moment. In Pew Research Heart surveys, the question asks: "In politics today, practise you consider yourself a Republican, Democrat or Independent?"

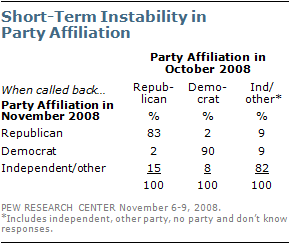

As the diction suggests, this question is intended to capture how people think of themselves currently, and people tin change their personal allegiance hands. We continually run across prove of this in surveys that ask the same people almost their party affiliation at ii dissimilar points in time. In a post-election survey we conducted in November 2008, nosotros interviewed voters with whom nosotros had spoken less than 1 month earlier, in mid-October.

As the diction suggests, this question is intended to capture how people think of themselves currently, and people tin change their personal allegiance hands. We continually run across prove of this in surveys that ask the same people almost their party affiliation at ii dissimilar points in time. In a post-election survey we conducted in November 2008, nosotros interviewed voters with whom nosotros had spoken less than 1 month earlier, in mid-October.

Among Republicans interviewed in October, 17% did non identify every bit Republicans in Nov. Among Democrats interviewed in October, 10% no longer identified as Democrats. Of those who declined to identify with a party in October, 18% told the states they were either Democrats or Republicans when we interviewed them in November. Overall, xv% of voters gave a different reply in November than they did in Oct.

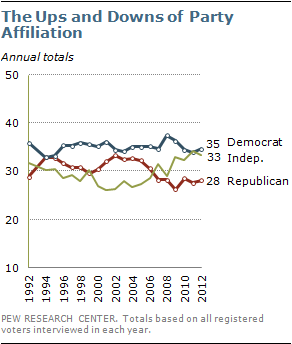

We likewise run across party affiliation changing in understandable ways over time, in response to major events and political circumstances. For example, the pct of registered voters identifying as Republican dropped from 33% to 28% between 2004 and 2007 during a flow in which disapproval of President George W. Bush's job performance was rising and opinions well-nigh the GOP were becoming increasingly negative.

We likewise run across party affiliation changing in understandable ways over time, in response to major events and political circumstances. For example, the pct of registered voters identifying as Republican dropped from 33% to 28% between 2004 and 2007 during a flow in which disapproval of President George W. Bush's job performance was rising and opinions well-nigh the GOP were becoming increasingly negative.

Similarly, the percent of American voters identifying equally Democrats dropped from 38% in 2008 – a high indicate not seen since the 1980s – to 34% in 2011, subsequently their large losses in the 2010 congressional elections. (For more about the fluidity of party affiliation, encounter Section 3 of the study, "Independents Oppose Political party in Power… Again," Sept. 23, 2010.)

The changeability of political party affiliation is one key reason why Pew Research and most other public pollsters do not attempt to adjust their samples to match some independent approximate of the "true" residual of party affiliation in the country. In addition, dissimilar national parameters for  characteristics such as gender, historic period, teaching and race, which can be derived from large government surveys, in that location is no independent estimate of party affiliation. Some critics argue that polls should exist weighted to the distribution of party affiliation every bit documented by the leave polls in the near contempo ballot. Only the employ of exit poll statistics for weighting electric current surveys has several issues.

characteristics such as gender, historic period, teaching and race, which can be derived from large government surveys, in that location is no independent estimate of party affiliation. Some critics argue that polls should exist weighted to the distribution of party affiliation every bit documented by the leave polls in the near contempo ballot. Only the employ of exit poll statistics for weighting electric current surveys has several issues.

First of all, a review of exit polls from the by iv elections (including midterm elections) shows the aforementioned kind of variability in party affiliation that telephone opinion polls show. Why is an get out poll taken well-nigh two years earlier a more than reliable guide to the current reality of party affiliation than our own survey taken correct now?

Second, most pollsters sample the general public – even if they later base their election estimates on registered voters or likely voters in that poll. Just the exit polls are sampling voters. We know that the distribution of party amalgamation is not the same among voters as it is amid the general public or among all those who are registered to vote. How tin can the exit polls provide an accurate target for weighting a general public sample when they are based on merely about half (or less) of the general public?

Registered Voters vs. Likely Voters

Some other common question during election years is why nosotros report on registered voters when we will ultimately base our election forecast on likely voters. We certainly empathise that the best approximate of how the election volition turn out is one that reflects the voting intentions of people who will actually vote. Most – merely not all – people who are registered to vote cast a election in presidential ballot years. It is for this reason that pollsters, including Pew Research, brand a substantial try to identify who is a probable voter (For more details on how likely voters are determined, see "Identifying Likely Voters" in the methodology section of our website).

Some other common question during election years is why nosotros report on registered voters when we will ultimately base our election forecast on likely voters. We certainly empathise that the best approximate of how the election volition turn out is one that reflects the voting intentions of people who will actually vote. Most – merely not all – people who are registered to vote cast a election in presidential ballot years. It is for this reason that pollsters, including Pew Research, brand a substantial try to identify who is a probable voter (For more details on how likely voters are determined, see "Identifying Likely Voters" in the methodology section of our website).

Only, in the same way that party affiliation is not fixed for a given individual, beingness a "probable voter" is not a demographic feature like gender or race. Political campaigns are, in part, designed to mobilize supporters to vote. Although it may experience like the presidential campaign is in full swing, much of the hard work of mobilizing voters has non nevertheless taken identify and won't occur until much closer to the election. Accordingly, whatsoever conclusion of who is a probable voter today – iii months before the election – is apt to contain a pregnant corporeality of fault. For this reason, Pew Research and many other polling organizations typically do not written report on likely voters until September, after the nominating conventions accept concluded and the campaign is fully underway.

Critics have argued that whatever poll based on registered voters is likely to be biased toward Democratic candidates, since likely voter screens tend to reduce the proportion of Democratic supporters relative to Republican supporters. This has been the case in Pew Inquiry's final election polls over the past 4 presidential elections. In these polls the vote margin has been, on boilerplate, 5 points more favorable to the Republican candidates when based on probable voters rather than registered voters. These last estimates of the upshot have more often than not been very accurate, especially when undecided respondents are allocated to the candidates.

Yet the upshot of limiting the analysis to likely voters tin vary over the course of the campaign bicycle, even in just the later months. For example, in September and Oct of 2008, most Pew Research surveys found little difference between election estimates based on all registered voters and those nosotros identified every bit most likely to vote, suggesting again that determining a probable voter gets more accurate only as Election Day nears.

If All Registered Voters Voted Along Party Lines, Who Would Win -- Democrats Or Republicans?,

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2012/08/03/party-affiliation-and-election-polls/

Posted by: torreshorlsonflon.blogspot.com

0 Response to "If All Registered Voters Voted Along Party Lines, Who Would Win -- Democrats Or Republicans?"

Post a Comment